What’s the context?

Undocumented immigrants already struggle to carry enough water on scorching desert routes. Now rising temperatures are making them more deadly yet

- Migrant crossing and fatalities spike on U.S. border

- Many struggle to carry enough water for desert trek

- Extreme heat threatens increase in deaths, say researchers

MEXICO CITY/WASHINGTON – Weighed down with four liters of water, Mexican Alfredo Cázares embarked on a risky, illegal journey across the U.S. border and into the sweltering Arizona desert beyond.

The construction worker was able to withstand the thirst during the two-day trip, but most of the others in his 15-person group became too dehydrated to keep walking.

“Those who couldn’t continue were left behind in the middle of the road where they had to wait to be found by the border patrol,” Cázares, 31, who was caught and deported, told Context by phone from the central Mexican city of Puebla.

As migrant crossings over the southern U.S. border increase, some academics and humanitarian groups are warning that rising temperatures could lead to more deaths on the perilous route.

The U.S. border patrol reported a record 2.2 million encounters with migrants along the border with Mexico in the fiscal year 2022, which ended in September. It was the first time the numbers exceeded two million per year.

Migrant deaths along the border also spiked to a high of 727 last year, according to data compiled by the International Organization for Migration (IOM), while more than 450 deaths were recorded in the first 10 months of 2022.

Exposure to harsh environmental conditions is the second most common cause of death on the border, the IOM found, second only to drowning.

Separate records held by Mexico on the deaths of 4,707 migrants on the border between 2009 to June 2022 found that dehydration was the most common cause of death.

Not enough water

The migration wave on the U.S. border has been mainly driven by people fleeing economic and political turmoil in Venezuela, Cuba, and Nicaragua, and fuelled by a reduction in legal U.S. asylum options in recent years and promises of a “more humane” border policy under President Joe Biden.

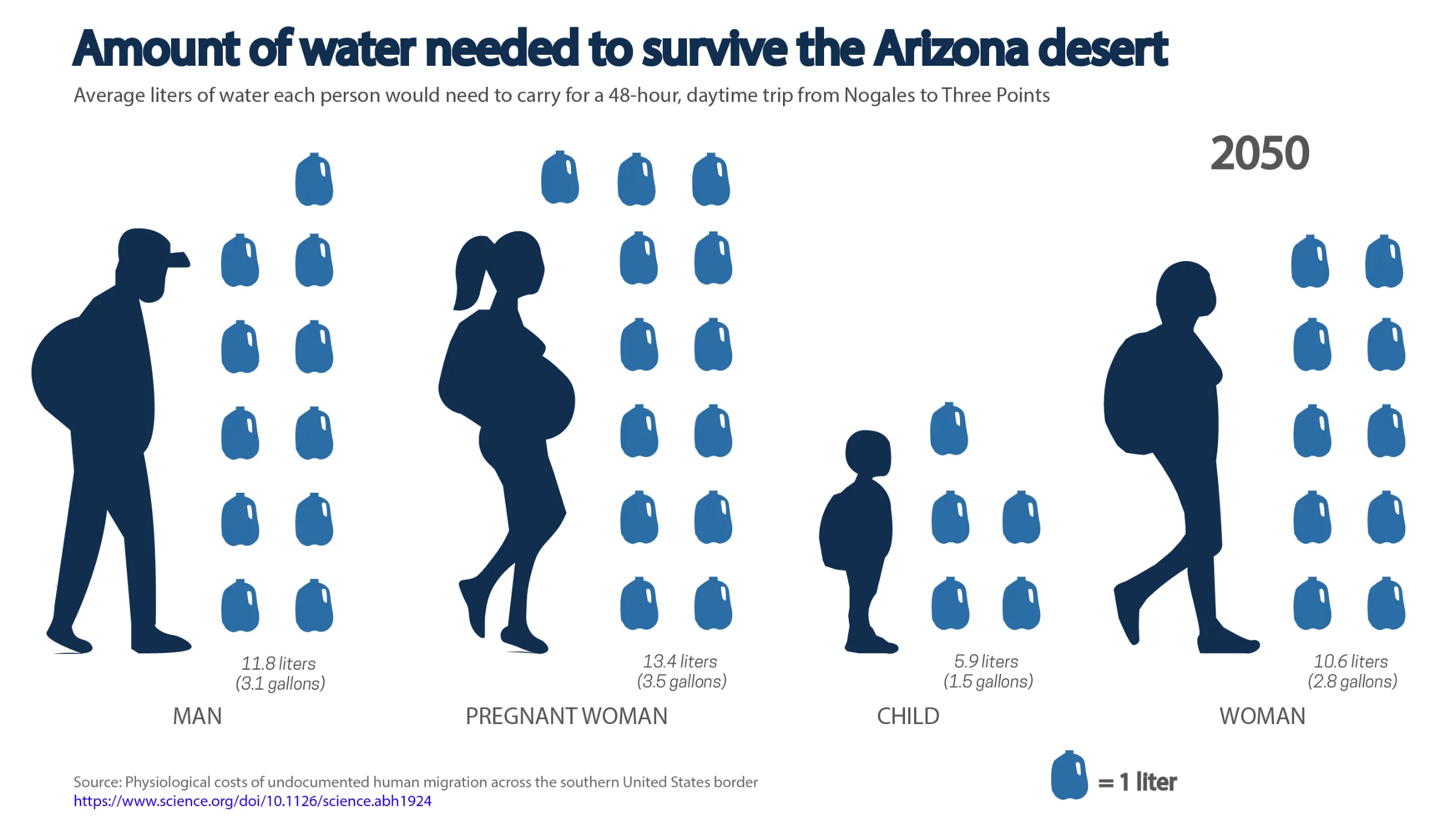

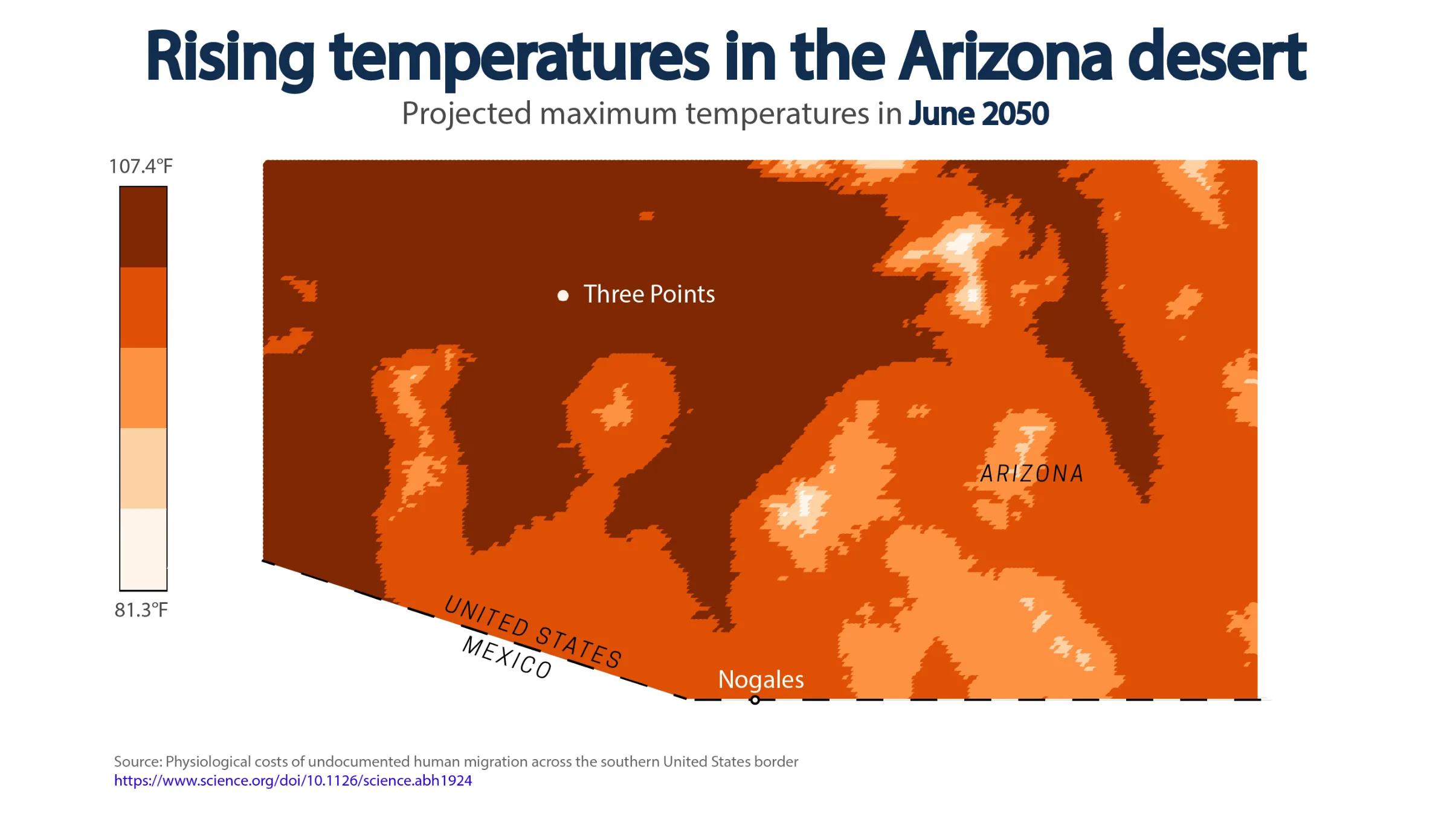

Many attempt to cross from the Mexican border city of Nogales to Three Points in Arizona, a perilous journey across the arid Sonoran desert where temperatures often reach 118 degrees Fahrenheit (48 degrees Celsius).

On average, it takes them 48 hours, or longer if they get lost or take longer routes in an attempt to dodge border patrols.

But most migrants do not have the strength to carry enough water to stay safe, say researchers and humanitarian groups.

“You can’t carry enough supplies … even at nighttime, it’s still around 100 degrees,” said James Cordero, of humanitarian organization Border Kindness.

The last 21 years have been the warmest on record for Arizona, where temperatures have increased about 2.5F since the beginning of the 20th century, according to the 2022 State Climate Summary.

It added that “recent upward trends in average temperatures and extreme heat” are likely to continue.

“The desert just never has the time to cool off so people don’t have time to cool their core body temperatures, and I believe that’s having a greater impact all along the border,” Cordero said of the recent spike in migrant deaths.

Border Kindness is one of several citizen-led initiatives that leave water and food in the desert for migrants.

Impossible burden

A first-of-its-kind study found rising average surface temperatures on paths taken by migrants in the Arizona desert will lead to faster dehydration, and are likely to increase the number of fatalities.

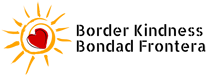

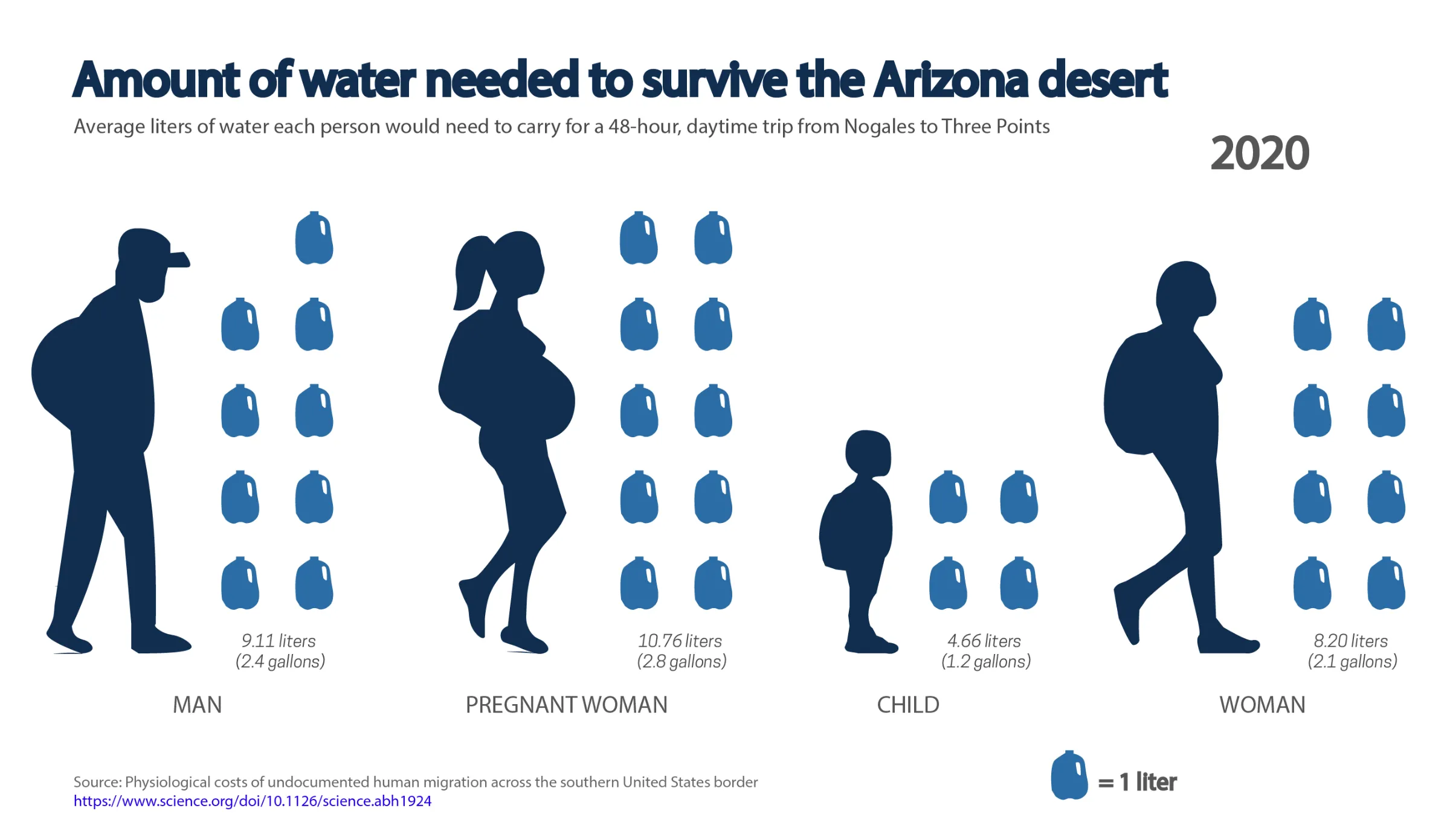

Researchers estimated how much water migrants need for a two-day crossing between Nogales and Three Points in temperatures of 91-104F (33-40C) – and how much if temperatures rose between 1.8-7F by 2050.

Migrants will be forced to carry about a third more drinking water to stay hydrated by 2050, found the research, published in the peer-reviewed Science journal in December.

“It’s not trivial … It’s impossible to carry the amount of water you need,” said Ryan Long, an associate professor of wildlife science at the University of Idaho who was one of the study authors.

“What that means is that more people are going to die.”

Weaponized climate

Experts warned U.S. strategies to discourage undocumented migration are increasing the heat risks to migrants by pushing them away from direct roads and water stations.

Since 1994, the U.S. border control’s Prevention Through Deterrence program has attempted to dissuade undocumented migrants from crossing by redirecting them into remote areas.

“(Prevention Through Deterrence) is in a way weaponizing a combination of climate and topography, the remoteness of the desert, to keep people from crossing the border,” said Long.

Rising heat under climate change should prompt a rollback of the program and a shift to prioritizing saving lives on the border, Human Rights Watch and other rights organizations said in an open letter to Biden last year.

The U.S. Customs and Border Protection force said the blame for deaths lay with people smugglers.

“Smuggling organizations are abandoning migrants in remote and dangerous areas, leading to a rise in the number of rescues but also tragically a rise in the number of deaths,” a spokesperson said.

Cázares said despite paying a smuggler to help him cross the border, his group was lost in the desert most of the time as they tried to avoid getting caught.

In two days, he only made it halfway to Three Points before he was discovered by a border patrol drone.

Despite the dangers, Cázares is saving to pay a smuggler for another attempt.

“I know something bad can happen on my way there, but I am determined to try again,” said Cázares.

(Reporting by Diana Baptista in Mexico City and David Sherfinski in Washington; Editing by Sonia Elks.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.